I think interest rates—now at historic lows—are going to remain low (perhaps with some transitory upticks for inflation) for a very long time. And that means that it will be harder, that is, it will cost more, for Americans to retire.

Here’s why.

Here’s why.

The Impact on Retirement(s)

Let’s begin with why interest rates matter for retirement. Here are three big reasons:

First, interest rates and the returns to other assets are necessarily correlated. At an intuitive level, if interest rates are “too high,” then investors will prefer bonds to stocks, driving bond prices up and rates down. If they are “too low,” then the reverse will happen; indeed, investors will borrow to invest in stocks, driving rates up and bond prices down. Thus, the returns to savings are driven by interest rates.

Second, interest rates represent the price of certainty. As (in our aging society) individuals approach retirement, they prefer certain (bond) income over uncertain equity returns. Thus, the price of annuities (the ultimate retirement benefit) is directly linked to interest rates.

Third, they are the critical variable in any valuation (that is, the critical variable in any present value formula). Thus, changes in interest rates result in changes, e.g., in liability valuations in defined benefit plans and in stock market valuation. Indeed, as former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has pointed out, much (if not all) of the rise in stock prices may be attributed to the decline in interest rates. The math here is simple: the stock market represents, to a large extent, the present value (capitalization) of expected future earnings. As interest rates go down, the value of all income producing assets (not just bonds) goes up, and (completing a circle) the earnings rate (e.g., earnings per share) goes down.

Interest Rates Represent the Price of the Future

Indeed, in some very deep way, interest rates represent the price of the future. As rates go down, the cost of producing income in the future goes up. Or maybe the way to put that is, if rates go down, it means that the cost of producing income in the future has gone up. Why it has gone up is a different, more tricky, and disputed question.

Hint: it’s not the Fed.

So, Why Are Interest Rates So Low?

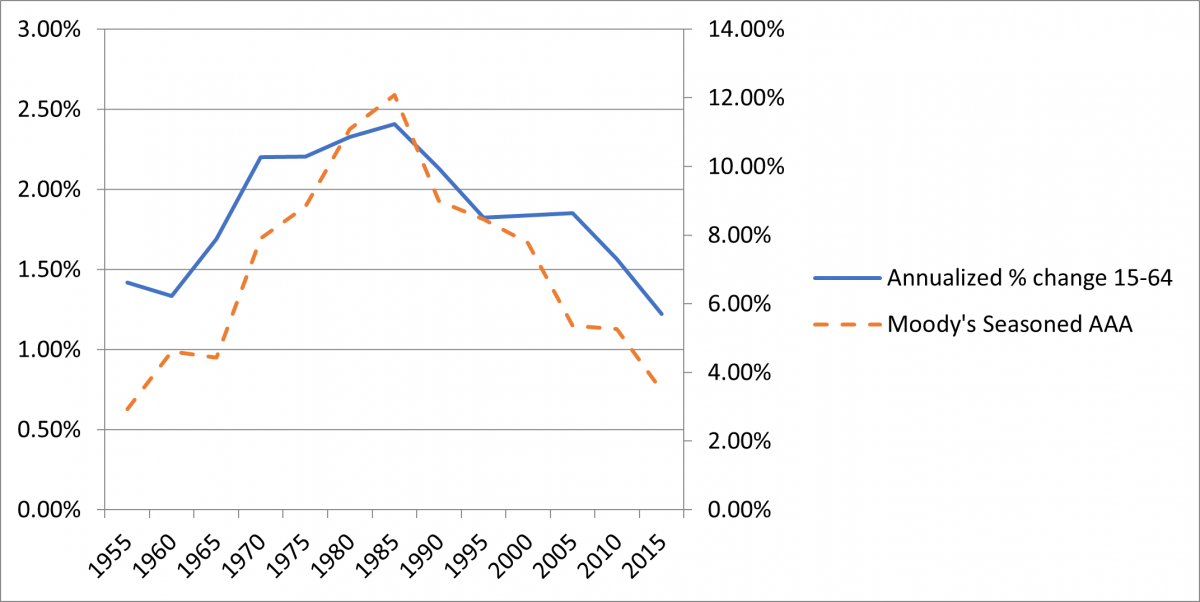

My “aha moment” on these issues came as I was thinking about why we have seen a long run decline in interest rates since the early 1980s, and I decided to map interest rates against population. The chart that froze me in my seat was this one, mapping US corporate bonds against the world working population growth rate.

The correlation here is uncanny.

In 2018, when I was writing my book (Retirement Savings Policy – Past, Present, and Future, De Gruyter, 2018) I reached out to Richard Jackson, President of the Global Aging Institute, and asked him if this correlation, between interest rates and population growth, was recognized in the literature. He said it was. Here (oversimplifying) is the neoclassical economics explanation: A critical input to GDP is total hours worked. Assuming no change in productivity, slower population growth translates into slower growth in hours worked and thus to slower GDP growth. In this situation, assuming no change in savings—that is, the same number of dollars are chasing a slower-growing amount of future income—interest rates will go down.

This cycle, however, should (in the neoclassical equilibrium) adjust—as the population ages, and retirees begin to consume rather than save, demand for savings will go down and interest rates will go back up.

That hasn’t happened. Quoting Mr. Jackson: “At least to date, the impact of demographic change on the numerator [lower GDP growth] in the equation appears to have overwhelmed its impact on the denominator [lower savings demand].”

In this regard, I would observe that the recent census numbers indicate that the fertility rate in the United States (at least) is still going down.

So why aren’t we equilibrilating?

Beneath the Numbers, a Very Human Reality

I would tell a slightly more colloquial story, with a couple of non-neoclassical add-ons.

If we are going to have fewer working people in the future, one (or both) of two things must be the case: (1) the cost of labor will go up, and there will be a shortage of individuals prepared to provide services to the aging population; or (2) we will experience a radical increase in productivity (as in, robots for everything).

If, as seems likely, (1, labor shortage) is the case, then having-more-money-in-the-future, when the competition for labor will be more intense, may (at the extreme) be more valuable than having money today (reversing the “time value of money”). Less extremely, having-more-money-in-the-future is clearly a lot more valuable than it used to be, which is why interest rates are so low. And not going back up.

More speculatively, I would say that increases in productivity, and at some gut level GDP growth, is not just a function of hours worked. It’s also a function of what Keynes called “animal spirits” —of youth and new ideas and a spirit of adventure (sometimes to the point of recklessness). Ideas beget enterprises, and enterprises need financing (with bonds), based on the promise of greater future earnings. These all put upward pressure on interest rates.

This is not the world we live in: ours (in the first world at least) is a world getting older. And definitely less reckless.

(On these and related issues I highly recommend Richard Jackson’s recent article ,"The Macro Challenges of Population Aging, in The Shape of Things To Come," The Concord Coalition & the Global Aging Institute, Spring 2021.)

Stop-Gaps

Immigration, which adds workers and hours worked without requiring a robust fertility rate, is (at best) a partial and temporary solution to this problem. Partial because it is difficult—switching cultures (e.g., the immigrant adapting to a different culture) necessarily costs something, though arguably easier in America than in a more insular country. Temporary because the fertility rate in rest of the world is also declining. This phenomenon seems to be a feature of modernity (I love this heat map from the UN showing population growth projections).

The other obvious solution is for everyone, or as many who can, to work longer. An increasing retirement age will add to the hours-worked input to GDP. This, of course, is just another version of retirement “costing more.”

A Widening Dependency Gap

The two phenomena—young-age and old-age—are linked, and bundled by economists into the concept “dependency.” More or less, children under age 16 are dependent on their (working) parents and old people over 65 are dependent on their (working) children (or someone else’s working children). (In the first world we might increase the lower bound of dependency to, say, age 18.)

But: that human life is bracketed by these long periods of dependency isn’t just a datapoint. It presents a deeper, human issue, a reciprocity between generations. Children taking care of their parents is a pay-back for parents taking care of their children, paying it forward as it were.

When a significant piece of a population doesn’t pay it forward, you’re going to have a problem. The United States ranks near the top (among nations) in childlessness—at around 20% in 2014. Our birth rate continues to decline. Our fertility rate is around 1.7—well below the replacement rate of 2.1.

One thing is certain—population growth can’t decline forever. You will either run out of people. Or the people that are left will start having babies.

At which point, interest rates may go up. And it may get easier to retire.

Michael P. Barry is a senior consultant at October Three and President of O3 Plan Advisory Services LLC, which provides retirement plan regulatory analysis targeted at plan sponsors and those who provide services to them.

Opinions expressed are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPPA or its members.

- Log in to post comments