The most powerful force in the Universe is compound interest. - Albert Einstein

In 1984, the Portland Trailblazers selected Sam Bowie over Michael Jordan as their draft pick—and as the saying goes, the rest is history. Although Sam Bowie was a terrific 7’3” center, his name has long been forgotten. In contrast, the Chicago Bulls were made famous by Michael Jordan, who retired over 20 years ago but is still well known. I imagine someone still loses sleep today over that fateful pick almost 40 years ago.

Sometimes, as in the case of the Trailblazers, we know when we make a mistake. Too often we remain unaware of our missteps, as is the case when public employees leave their pension early.

When public employees decide to switch to the private sector in the middle of their career, leaving their defined benefit plan behind has a significant impact on their financial situation for retirement.

Without a crystal ball, we can’t say precisely how much people leave on the table when they leave their pension mid-career. However, with a few key assumptions, we can estimate the significance of the financial decision.

Key Assumption #1: Raises

The first assumption we need to make is about the raises that would have been received if the plan participant had continued with their current employer. The analysis below reflects annual raises of 2%, 3%, and 4% for a participant who initially planned to retire after 30 years, and whose pension system provides the same crediting for each year of service.

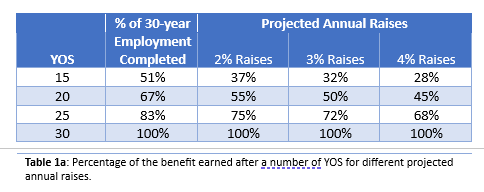

Table 1a presents the percentage of the pension they have earned after a specific number of years of service (YOS) with different annual raises. For example, a person leaving their job after 25 YOS (5 years earlier than planned) would have completed 83.3% of their 30-year employment, but with 2% raises would have only earned 75.5% of their benefit. In other words, they would lose almost 25% of their pension as a result of leaving just five years early. If annual raises are higher than 2%, the reduction in their benefits is even greater. Clearly, leaving just a few years earlier results in a significant loss of pension income.

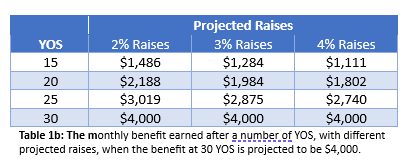

For those who prefer to see monetary values, Table 1b shows the individual’s monthly pension income pension with the various YOSs and various projected annual raises.

Key Assumption #2: Using a Tiered Crediting Formula

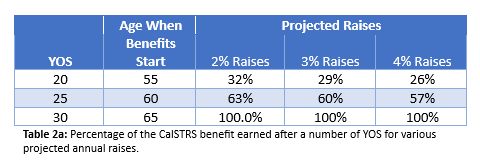

The illustration above assumes the same crediting for each year of service, but this is not always the case. For example, for employees in California STRS hired before 2013 (CalSTRS), crediting changes based on the age at which they retire. If they start to receive their benefits at age 55, 60, or 65, the percent crediting for each year of service is 1.4%, 2%, or 2.4%, respectively. Table 2a presents the percentage of income they will earn at different ages when benefits start.

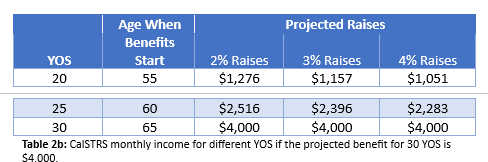

(If the plan participant wanted to keep the same benefit start age but leave CalSTRS, then the percentages from Table 1a would apply.) Table 2b presents the monthly income that same participant would receive for various YOS in CalSTRS.

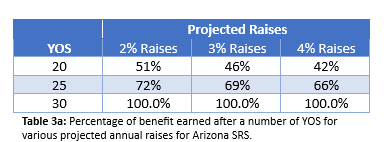

Arizona SRS is another pension plan with tiered crediting, but the tiers are based on the number of YOS (not age). (The crediting is 2.15% for less than 20 YOS, 2.2% for 20 to 25 YOS and 2.3% for 30 YOS). Table 3a shows the percentage of the benefit earned with various YOS.

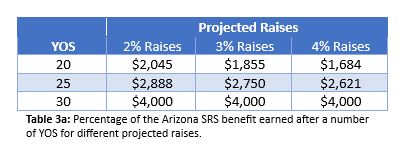

Table 3b presents the monthly income a participant is projected to receive based on various YOS if their projected benefit for 30 YOS is $4,000.

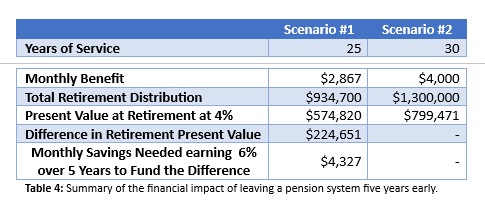

Let me drill down just a little bit more. (If your head is spinning from all the numbers, feel free to skip to Table 4 and the summary that follows it.) Suppose a plan participant expects 3% raises until retirement and has a projected benefit at age 60 of $4,000. The IRS life expectancy at age 60 is 27 years and one month (325 months). Without cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), the total payout over their life expectancy is $1,300,000. Using a 4% rate of return during retirement, the payout has a present value at retirement of $799,471. However, if they leave their employment after 25 years, their monthly benefit is $2,876 (71.9% of the benefit, from Table 1) or a total income of $934,700. The present value of this total income in retirement is $574,280—a reduction of $224,651.

This person leaving a defined benefit plan five years early would have to save $4,327 per month for the next five years to make up for the loss of income from their pension plan over their life expectancy. (This calculation does not consider any COLAs, which some pension systems provide.) This monthly savings target is well above the current participant 401(k) contribution limit and is more than the average Americans can afford to save.

In short, leaving a pension system even a few years early can significantly impact one’s financial situation in retirement. In this scenario, leaving the plan just one year early would require the participant to save almost a thousand dollars each month to recover the lost income. Many employees leaving public pension systems have little or no understanding of how early retirement affects their financial situation.

Making the Calculations Tangible

Percentages and generic dollar values are abstract, and therefore many people do not connect with them. Fortunately, we have a few ways to make these calculations more tangible for plan participants. One strategy is to calculate how early retirement would impact the participant’s projected retirement benefit:

Multiply the projected benefit by the percentage that they would receive, and then compare the two numbers. Another strategy is to use the participant’s current income instead of projected benefits. Yet another option is to calculate the total income they will receive in retirement and multiply it by the percentage by which they will reduce their income. This can show the real cost of leaving employment early. When people see their own values, they are able to understand the analysis in a more meaningful way.

Takeaways

The foregoing analysis teaches us three lessons:

1. Leaving a defined benefit system early can significantly impact one’s financial situation in retirement. Albert Einstein touched on this concept when he said, “The most powerful force in the Universe is compound interest.” In this case, we’re talking about compounded raises rather than compounded interest, but the principle is the same. Leaving even five years early can have a significant impact on one’s financial situation in retirement. Before anyone decides to leave their pension system, they need to have a good grasp of how it will impact their financial situation in retirement.

2. Knowing the details of pension systems is critical. Even different tiers in the same pension system can result in significant reductions in retirement income when people leave their plan early.

3. Abstract numbers and detailed analyses often confuse people. Making each analysis as specific as possible for each participant’s situation can help. Software can make this process easier. And, if it is designed well, software can also make the analysis more relatable.

Hindsight is 20/20, so it’s easy to call the Trailblazers’ decision foolish. Had they known the future, they certainly would have made a better decision.

Fortunately, we can help our plan clients avoid making similarly bad decisions. Helping clients understand the cost of their decisions can not only help them have a better future it can win financial advisors referrals from clients they have helped. While we cannot guarantee their future, we can project how certain decisions will impact plan participants’ future. And we can—and should—guide them toward a better understanding of the financial impacts of their decisions.

Ed Dressel is President, RetireReady Solutions.

- Log in to post comments