How do/should we “value” environmental and social governance (ESG) investments? Here’s how the Department of Labor (DOL) summarizes its final ESG regulation:

“The amendments [revising ERISA fiduciary rules to restrict ESG investments] require plan fiduciaries to select investments and investment courses of action based solely on financial considerations relevant to the risk-adjusted economic value of a particular investment or investment course of action.” (Emphasis added.)

The DOL’s effort to set limits on ESG investing implicates three ERISA duties—prudence, diversification and loyalty. For me the headline issue is prudence and (as DOL itself claims in what I just quoted) the question of value. And that is where I want to start unravelling this seemingly endless argument we’re having over “social investing.”

What Is Value?

Imagine that American investors fall in love with a particular industry—say, electric cars—because of the vision that industry presents—a world without carbon “pollution.” And because of this love, they all want to invest in electric car companies—not because of any hard-headed analysis of the “risk-adjusted value” of electric car companies’ future earnings, but because of this vision. And as a result, the price of the stock of electric car companies is bid up, vastly exceeding any theoretically rational P/E ratio.

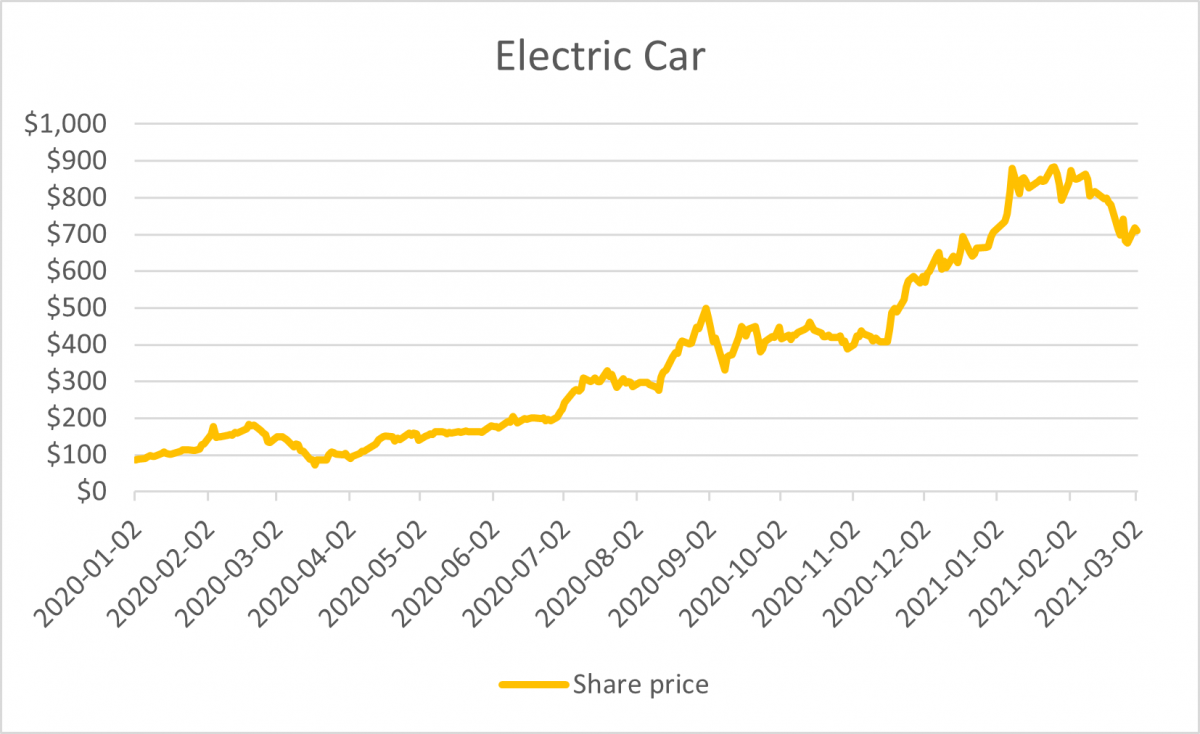

Say that the last year’s performance of Electric Car Corp. looks like this:

That’s around a 700% increase in share price in a little more than a year. And Electric Car’s stock now has P/E ratio of over 1,100. (For context, the S&P 500 P/E ratio is around 34.) Is this stock overvalued? How do you tell? Is there something wrong—under ERISA—with investing in Electric Car? Or, for that matter, a fund that invests in electric cars?

That’s around a 700% increase in share price in a little more than a year. And Electric Car’s stock now has P/E ratio of over 1,100. (For context, the S&P 500 P/E ratio is around 34.) Is this stock overvalued? How do you tell? Is there something wrong—under ERISA—with investing in Electric Car? Or, for that matter, a fund that invests in electric cars?

The DOL’s concept—“risk-adjusted economic value”—is not a viable basis for a rule-of-prudence, at least not in the context of publicly traded stocks.

And neither are the concepts “pecuniary” (mentioned 326 times in the regulation package) and “non-pecuniary.” Actually, anything the market puts a value on—Bitcoin, Beanie Babies or some exciting new technology—is pecuniary.

DOL’s Regulation vs. the Market

What’s wrong here? For better or worse, we no longer (since around the end of the 19th century) think about the value of, e.g., a share of stock of a particular issuer as somehow based on something inherent in the issuer. In the end, the only thing that matters in determining how much we will pay for a firm’s stock is (for publicly traded stocks) what the market says. And that is its value.

Presumably, the market will reflect the views of various investors, including their views about future earnings and the various stories about different trajectories for those earnings that analysts tell. But no one is going to be able buy a stock for less than it is currently trading for, even if they think it is overvalued.

So, if the market says Electric Car is worth $700 a share, even with an 1,100 P/E ratio, then that is what it is worth.

And vs. the Supreme Court

This point was made emphatically (and unanimously) by the Supreme Court in Fifth Third Bancorp et al. v. Dudenhoeffer:

“In our view, where a stock is publicly traded, allegations that a fiduciary should have recognized from publicly available information alone that the market was over- or undervaluing the stock are implausible as a general rule, at least in the absence of special circumstances. … In other words, a fiduciary usually “is not imprudent to assume that a major stock market . . . provides the best estimate of the value of the stocks traded on it that is available to him.”

Regarding this first issue addressed by the DOL’s ESG regulation—that plans may not overpay for ESG investments—I would say: an ESG investment purchased at market price is worth whatever that price is. Put another way: It would certainly be prudent to invest in the electric car, or an electric car fund, at some price. If that price is not the market price, then in what other way could you determine it?

This question of value is one-half of the ERISA prudence issue. The other half is diversification—which exists both as an element of prudence and as a separate duty under ERISA.

The ERISA Duty of Diversification

Diversification was not an issue in Dudenhoeffer—employer stock in defined contribution plans generally is exempted from ERISA’s diversification requirements.

In the interests of space, I’ll keep the discussion of this issue brief (and somewhat conclusory). When a DC plan provides a diversified menu of investment options, the fact that a single fund is not itself diversified does not violate ERISA’s diversification requirement. A rule requiring that the sponsor enforce the diversification of every participant’s portfolio would result in the elimination of participant choice plans.

With respect to qualified default investments, a different rule would obviously apply. The plan’s default QDIA (e.g., target date fund) should be diversified. But no one is proposing that all funds in a QDIA be ESG funds. In QDIAs, ESG funds function, in effect, as a theme. And, notwithstanding the DOL’s emphasis on the pecuniary vs. the non-pecuniary, the market obviously values ESG firms—just look at Electric Car.

A similar analysis would apply to investments in ESG funds by defined benefit plans.

Finally, let’s deal with one other topic that arguably is a diversification issue: negative “screeners,” as in, “our plan does not invest in tobacco companies.” Diversification, adequate to eliminate uncompensated “single stock” risk, can be accomplished with a fairly limited set of investments. And, again, these screeners simply seem to me to be implementing a “theme”—an active management decision that in the long run these screened-out companies don’t represent good investments. Who is to say that is wrong? Most of us don’t believe the future has been determined.

The ERISA Duty of Loyalty

In applying the ERISA duty of loyalty to purchases of public traded securities at market prices, I would say that it is not very useful to have a rule that is dependent on reading the minds of the responsible fiduciaries. That approach might find a violation where a fiduciary stated that she authorized an investment in a fund because she (personally) “just likes electric cars” and not find a violation where the fiduciary just kept his mouth shut.

I would agree that, in one dimension, as DOL says, the need for a “tie-breaker” occurs “very rarely” in practice. But in another sense, the market, and prices, turns everything into a tie-breaker. That is, if two funds are fairly priced by the market, then they are exactly equivalent.

This is not a question of a fiduciary, e.g., buying overpriced real estate from a relative. It’s buying stock traded in a public market at market prices. An inquiry into motives is not appropriate.

Doesn’t This Approach Invite Abuse?

In single employer defined benefit plans, where the employer is on the hook for any funding shortfall, the answer is no.

For DC plans, there is not a similar alignment of interests—participants are stuck with any losses they sustain from losses on (or underperformance of) ESG funds picked by plan fiduciaries. I would argue, however, that, when the fund menu provides sufficient non-ESG alternatives, and a participant who doesn’t believe the ESG story can construct a diversified portfolio, there is not a problem.

Not an ERISA Problem

For those of us—including myself—who are bothered by what seems to be the politicization of investment decisions, with Republicans trying to constrain and Democrats trying to encourage ESG investing, I would say, in the end, this isn’t an ERISA problem. It’s a problem of the socio-economic-political situation we are living through. And we’re not going to solve that problem with an ERISA regulation.

Michael P. Barry is a senior consultant at October Three and President of O3 Plan Advisory Services LLC, which provides retirement plan regulatory analysis targeted at plan sponsors and those who provide services to them.

Opinions expressed are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPPA or its members.

- Log in to post comments