Recently, we showed how the percentage of retirement savings from a worker’s paycheck required to finance an adequate retirement had — for a worker retiring in 2021 — gone up over 50% vs. the amount of a paycheck a worker retiring in 2000 had to save.

In this article we’re going to look at the future — how much of their paycheck will participants retiring in the future have to save to finance the same adequate retirement as those who have retired in the past? For this purpose, we must make assumptions regarding the future behavior of relevant variables. Our baseline “pro forma” assumptions (as of August 2022) are:

- No change in life expectancy

- No change in interest rates

- 8.0% annual return on S&P 500

- 4.5% annual return on bond portfolio

- 2.5% annual increase in CPI

- 3.5% increase in National Average Wage

- 3.3% increase in median wages

- Current Social Security law (increases full retirement age to 67 by 2025)

For each retirement cohort, we assume workers begin saving for retirement at age 25 while earning the median wage for that year and retire at age 65 earning 200% of the median wage.

To test the sensitivity of future outcomes against different capital market scenarios, we also consider scenarios in which the S&P 500 earns an annual return of 4% or 12% per year over the next decade. Such changes have almost no effect on those retiring in 2023 and little effect on outcomes for those retiring in 2032. Bottom line: for workers retiring in the near- and medium-term, the die has largely been cast.

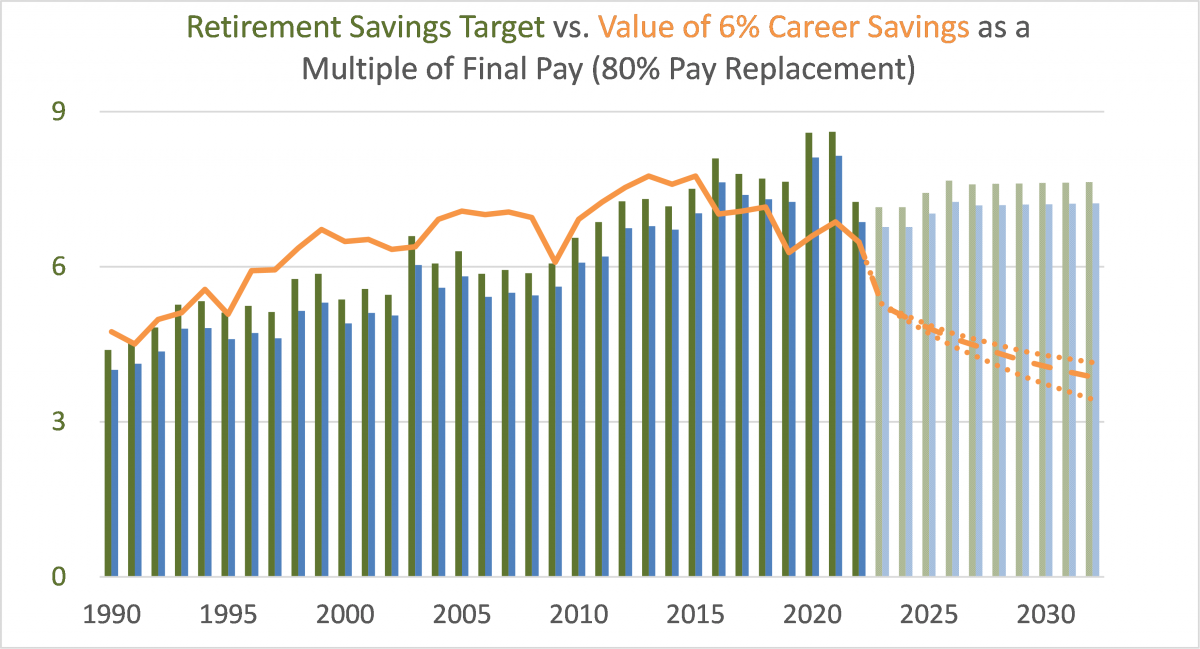

The following chart maps a 6% of pay savings + target date fund investment strategy (line graph) against the amount needed to buy an adequate (80% replacement) retirement income (bar graph).

As the chart shows, this 6% of pay savings strategy held up for workers retiring up to 2015. After 2015, however, it increasingly falls short. While the accumulation targets (bar graph) peaked in 2020-2021 as interest rates bottomed out, the capital market "ammunition" (target date fund returns) delivers less and less for the same level of savings.

That last point bears repeating: In the future, the same amount of savings will buy less income. That in a nutshell is the story the data (and our economy) is telling us.

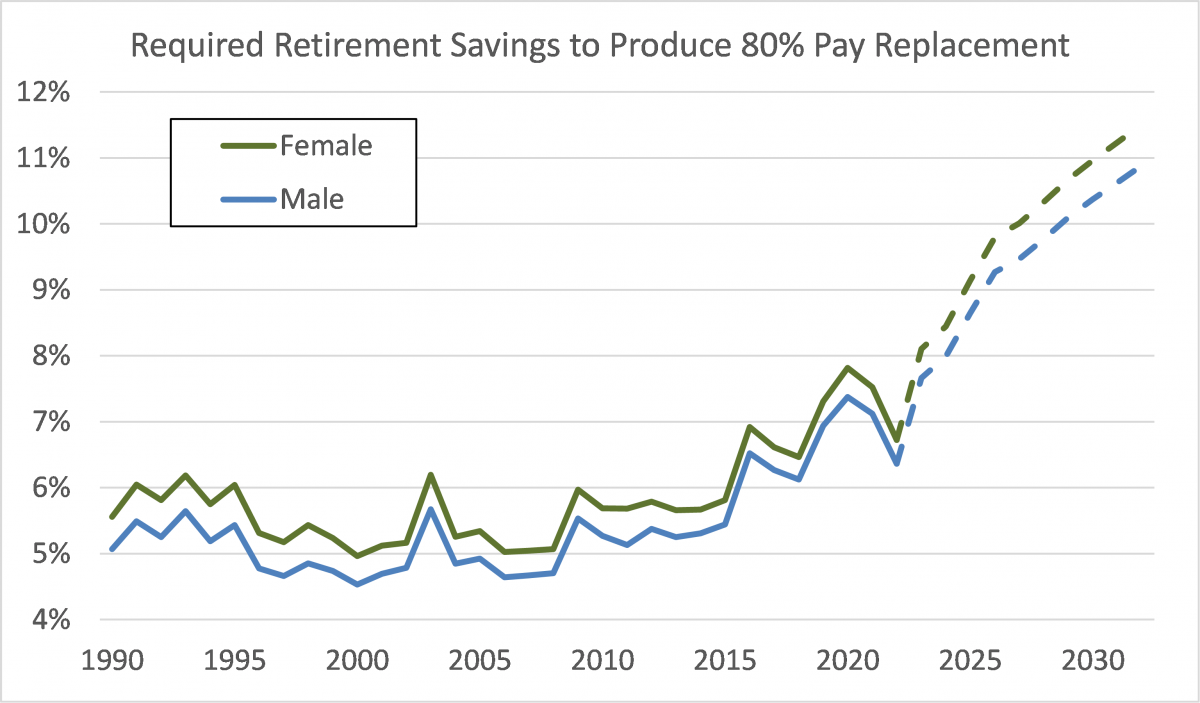

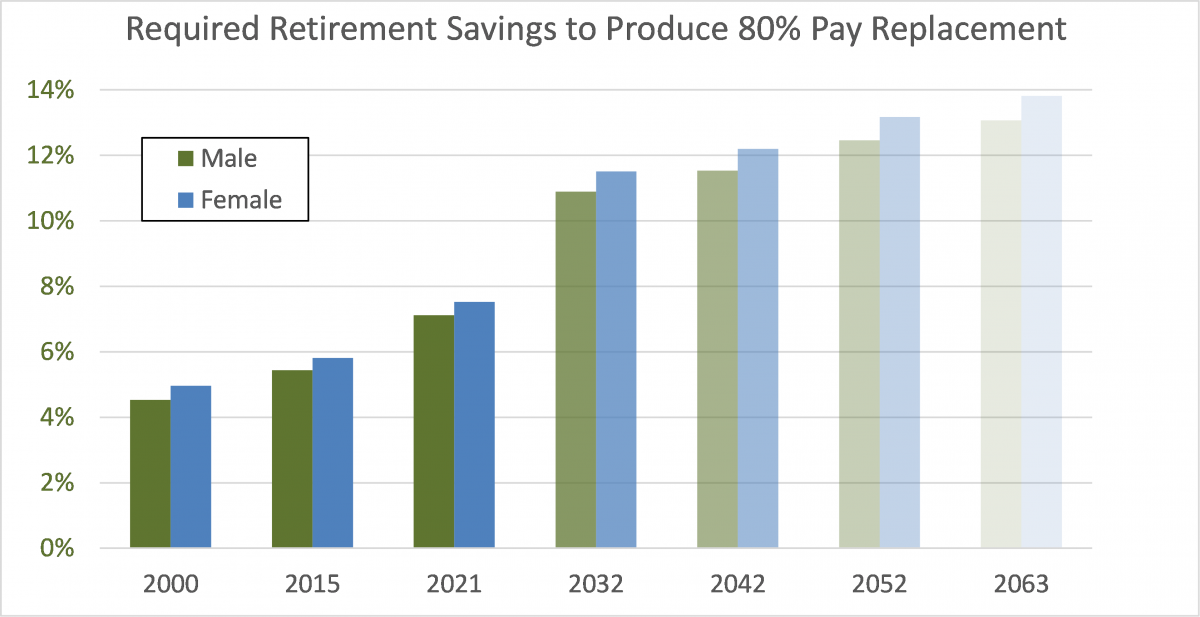

How much will future retirees have to save to produce adequate retirement income? The chart below illustrates the expected path of required savings for successive cohorts over the next decade:

What we see here is the impending fulfillment of the long-predicted “retirement crisis.” A current 55-year old female, born in 1967 and expecting to retire in 2032, will need to have saved 11.5% of pay, year in and year out from age 25, and invested those savings in a target date fund, in order to enjoy an “adequate” standard of living in retirement comparable to what a female born in 1950 could achieve by saving 5.8% of pay, a doubling of the cost of retirement over a 17 year period.

These are pro forma results are based on a straight-line extrapolation of current conditions. Actual results will surely be bumpier, but for those near retirement, most of the chapters have been written, and the trend toward higher retirement costs will almost surely continue. Even if stocks earn 12% per year over the next decade, a female retiring in 2032 would still need to have saved 10.5% of pay every year of her 40-year career.

Looking Deeper into the Future

If we continue the straight-line projection beyond 2032, the numbers get even worse, as shown in the chart below, which includes sample actual outcomes through 2021 and (progressively paler because more speculative) forecasts of retirements out to 2063:

Are We Exaggerating the Problem?

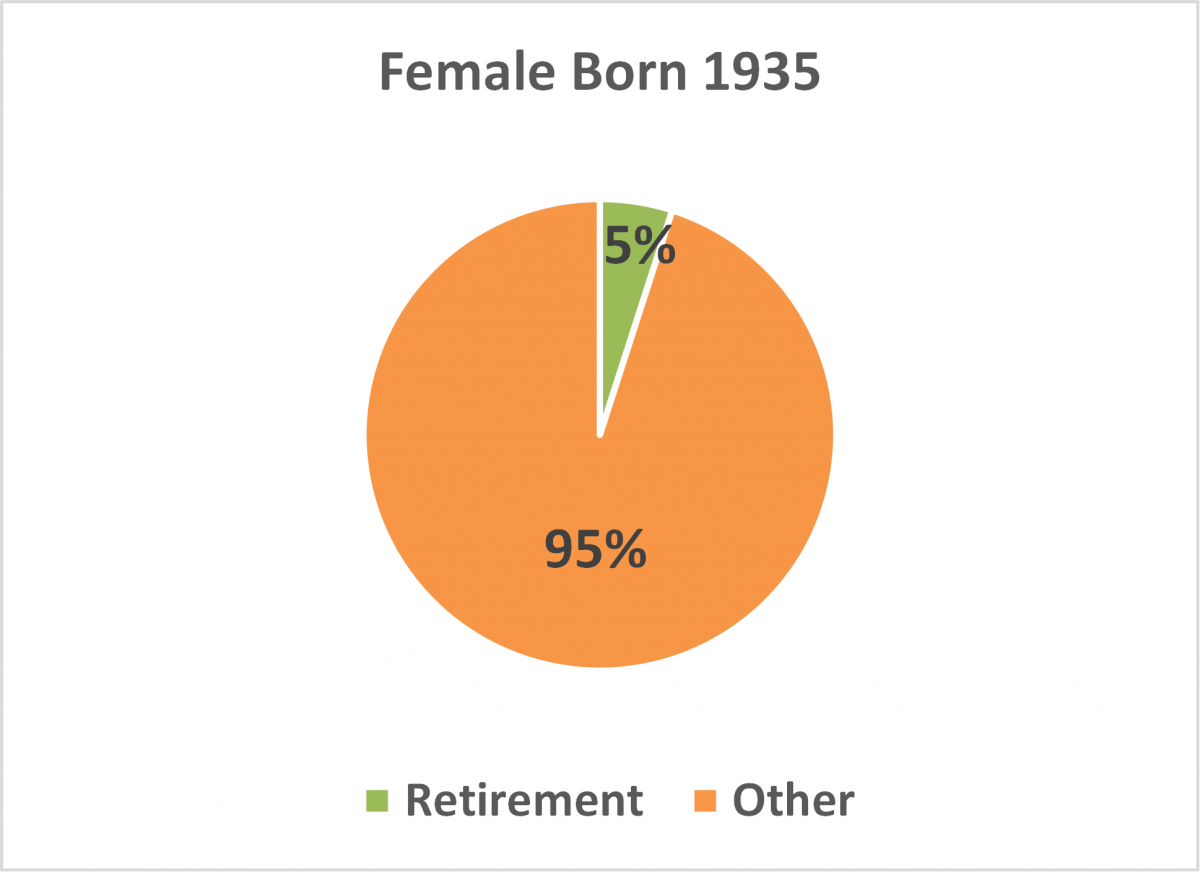

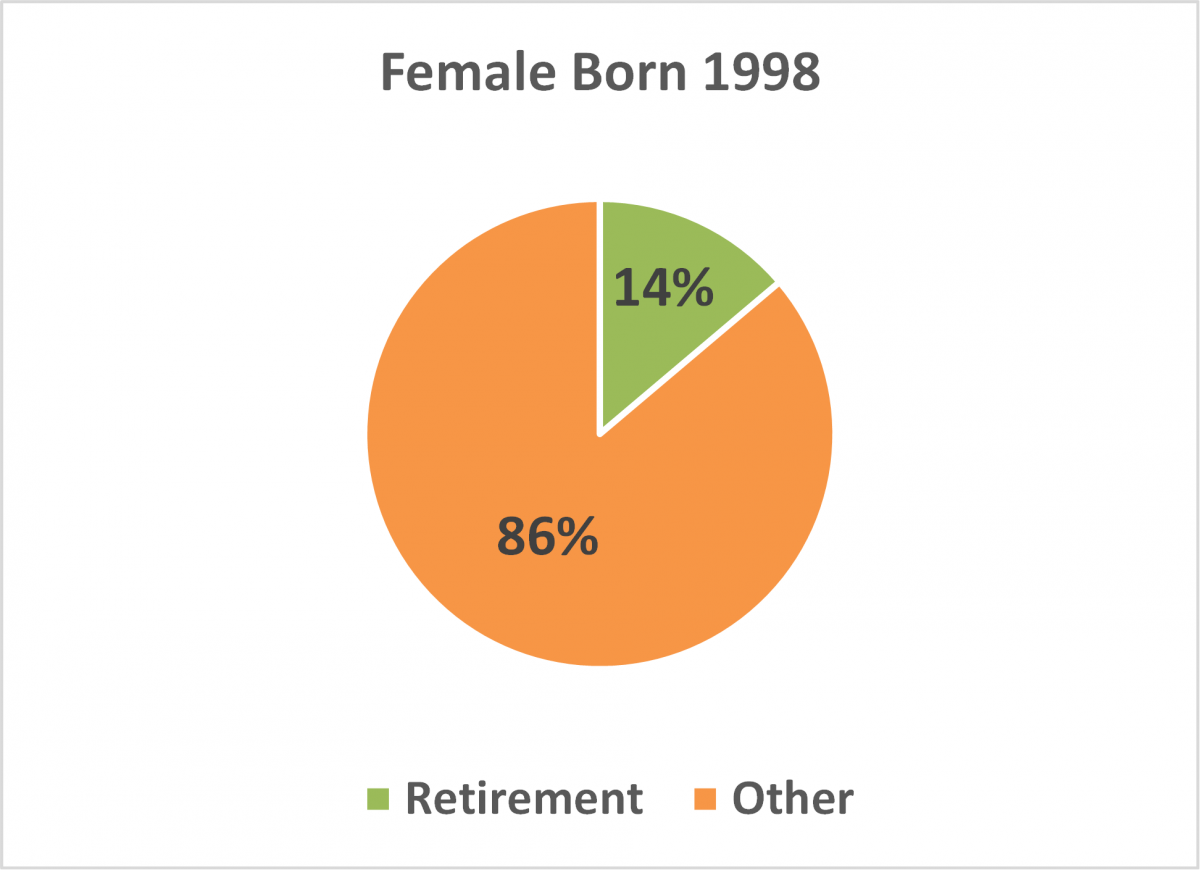

For individuals just entering the workforce today, and expecting to retire in 2063, the outcome is based entirely on the assumptions we describe above. No actual data beyond (current, August 2022) starting conditions is reflected. These numbers suggest a tripling of the cost of retirement compared to someone born in 1935 who retired in 2000.

Obviously, this estimate is only as good as the assumptions used. In general, we think the assumptions we used (2.0% real yield, 3.5% equity risk premium, no change to life expectancy or Social Security) will if anything tend to underestimate the cost of financing retirement in the future.

What Explains this Result?

What we are seeing in these numbers is the long run effect of the secular decline in interest rates. Interest rates affect the retirement finance equation in at least three ways:

- Declining interest rates increase the cost of retirement income. When interest rates go down, the amount of retirement income you can buy goes down.

- Declining interest rates increase the value of financial assets. When interest rates go down, bond values (in a saver’s portfolio) go up.

- A similar effect occurs regarding equities (assuming no downward revision in earnings projections) — when interest rates go down, the stock market P/E (price/earnings) ratio goes up.

Thus, for workers with significant retirement savings in their portfolio, the increase in the cost of retirement income associated with a decline in interest rates may be offset by an increase in the value of their portfolio. Indeed, defined benefit plan sponsors will often seek to offset the risk of “losses” due to interest rate declines by creating a duration-matched bond portfolio. That is called liability-driven investment (LDI).

The story of retirement savings for the period 1990-2021 (described in the above chart) is (by and large) the story of declining interest rates, offset (at least until around 2015) by increasing financial asset values.

Our somewhat shocking answer to the question, “How much does a new worker need to save for retirement?” simply reflects the reality of the cost of retirement savings in a stable, relatively low (4.5%) interest rate environment.

Current workers/savers will (in this low interest rate environment) not benefit from an increase in asset values resulting from interest rate declines — indeed, at this point interest rate declines will probably make the situation worse. Instead, a worker must produce an 80% (net of Social Security) pay replacement based on (1) a high cost of retirement income and (2) modest capital market performance.

Saved by Technology?

Our conclusion — that an “average” young worker today needs to save nearly three times as much, as a percent of pay, as a similar worker retiring in 2000 needed — is sobering. But the calculations are all based on assumptions.

If we hold all other assumptions constant, we calculate that today’s 25-year-old would need to earn 15% per year (for 40 years!) on S&P 500 investments in order to achieve their retirement objective based on saving 6% of pay per year. Such a scenario may occur, although it would likely involve a massive technological breakthrough such as nuclear fusion, which doesn’t strike us as a sound basis for a “retirement security” strategy.

Higher Interest Rates?

The increase in interest rates the past two years has reduced the cost of retiring modestly since 2020, but near-term projections indicate this good news is temporary, and even reflecting today’s higher interest rates, the total cost of retirement will increase over the next decade.

We believe that interest rates are likely to remain at current levels (or drift lower) for the foreseeable future. In this regard, we need to say something about inflation — an issue we’ve ignored so far.

Inflation generally “washes through” this analysis with little real effect (although, like stock market returns, there are idiosyncratic effects on individual retirement cohorts). That is, while inflation will drive up interest rates and reduce the (nominal) cost of retirement income, it will also increase the retirement income target (as wages inflate) and reduce buying power.

But what if “real” interest rates increase over the period 2022-2063?

In our next article, we will consider this possibility in a number of different respects, including the effect of increasing interest rates on financial assets and annuity purchase rates. We will also consider what fundamental conditions might lead to an increase in real interest rates. And we will consider the effects of inflation in more detail.

Michael P. Barry is a senior consultant at October Three and President of O3 Plan Advisory Services LLC, which provides retirement plan regulatory analysis targeted at plan sponsors and those who provide services to them.

Brian Donohue is a member of October Three’s actuarial consulting team and part of the senior leadership for October Three.

Opinions expressed are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPPA or its members.

- Log in to post comments